On Mining

San Francisco’s nineteenth-century founders built their city at Chrysopylae by exploiting natural resources. In a period where income per head tripled in thirty years, these men laid the foundations for today’s prosperity by creating an environmental cataclysm. By contrast, the West’s modern rulers refuse to make environmental or social concessions in the pursuit of long-term economic growth. The pendulum should swing back: in order to replicate the industrial advances that built the West and assure a second American century, Western leaders will have to make real sacrifices once again - most importantly, by granting permits and defeating legal obstacles to enable once again the extraction of America’s natural resources.

Jim L. Bowyer's 2016 book The Irresponsible Pursuit of Paradise lays down the gauntlet. With American resource extraction blocked, the undeniable burden of resource extraction falls on the rest of the world. If America won’t mine its own resources, China will flay the Third World for them instead. The social and environmental costs that campaigners deplore at home are exported to countries less able to bear them. Thanks to the twin horns of free-market globalisation and environmentalism (two movements, it must be said, with much credit to their name), America has sacrificed economic security while inflicting ecological damage on the Global South. There is a woke argument for reindustrialising America!

Imperial San Francisco, geographer Gray Brechin’s 2006 book, chronicles the impact of nineteenth-century urban development on the city’s surrounding contado. San Francisco’s growth was kick-started by the 1848 discovery of gold at Sutter’s Mill and the 1859 discovery of silver in the Sierras, with mining activity peaking in 1876. Banks and skyscrapers were built to fund the exploration; ironworks grew south of Market Street; Golden Gate Park was laid out in envy of Central Park.

Just as the city’s hills were tamed with graders and streetcars, so too was the wider contado: the Bay, the Sacramento Valley, and the Sierras were all reshaped to fuel the imperial city. Hawaii, Mexico and the Philippines became the objects of wars launched from the Bay’s dockyards and armouries. Iron water cannons, or “monitors”, carved up the gravel of the Sierras, but no less did they carve the canyon of California Street; indeed, early steel-framed skyscrapers, like the 1929 Shell Building just off Market Street, echo in their structure the heavy wooden “square set” cubes invented by Philip Deidesheimer in 1860 to mine the wide ore of the Comstock Lode.

The Shell Building, and Deidesheimer’s cubes.

With subheadings like “A Promised Land Plundered” and “The Sierra Flayed”, Brechin’s book examines “the long-ignored costs of city building.” These costs originate in a single invention. In 1853, Edward E. Matteson used a canvas hose with wooden nozzle to blast a gold-bearing bank with water: the mud and gravel washed down into a panning system that separated off the gold flakes. As Brechin puts it:

Matteson's primitive nozzle evolved into cast-iron hydraulic cannons known as monitors... Though it required large capital investment, hydraulicking greatly reduced labour costs. A single man operating a counterweighted water cannon mounted on a swivel joint could do the work of dozens of miners. With the air of bonfires and railroad headlamps, the mines operated round the clock. If a headwall proved resistant, well-placed explosives loosened it so that monitors could reduce it to thousands of tons of mud, gravel, and sand.

Monitors at Omega Mine, Washington Ridge - History of Tahoe National Forest

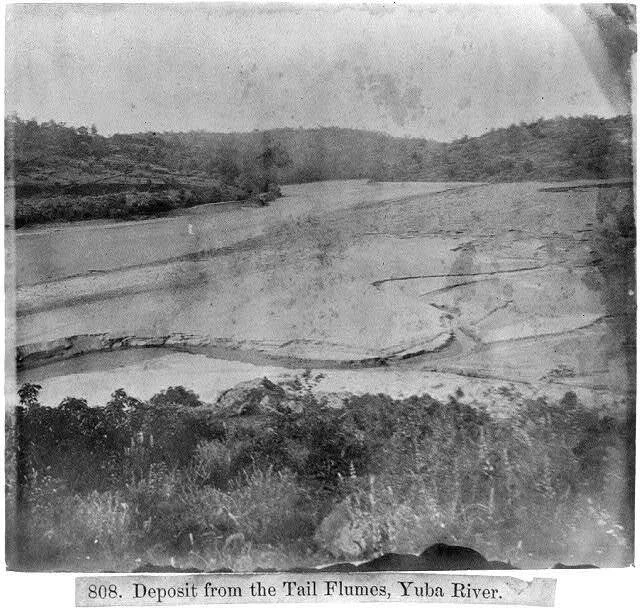

The monitors needed water, and so by 1859, 5,726 miles of canals, ditches, and wooden flumes had been dug across the Sierra. All this hydrological engineering had consequences: by 1874, a few years before the peak of mining activity, the bed of the Yuba River (whose watershed encompasses much of the Sierra) was up to sixty feet higher than it had been in 1849. Over this period, 1.7 trillion litres of mud and gravel were washed into the San Francisco Bay, making large sections of the north bay unnavigable. The Mare Island naval base was cut off: the Army Corps of Engineers had to dredge a channel to it: as Brechin puts it, this effort "grew ever more pharaonic… The industry's deferred costs sank into a rising sea of federal red ink and became agreeably invisible to those chiefly responsible."

Industrial economic development is impossible without power; and power was hard to come by in San Francisco. Northern California does not have significant coal or oil reserves. When San Francisco’s streets were first lit in 1854, the gas that fed the system had been refined from a shipment of Australian coal. In 1881 San Francisco consumed 868,000 tonnes of the stuff - a paltry sum when compared with the c. 175 million tonnes produced in Britain in the same year.

Only with Edward Doheny’s 1892 discovery of oil in Los Angeles itself did California’s petroleum industry begin to accelerate. In 1894, wells in Los Angeles produced 729,000 barrels, en route to a 105x increase in production across the entire state from 1890 to 1903. By 1911, California was producing 63% of America’s oil.

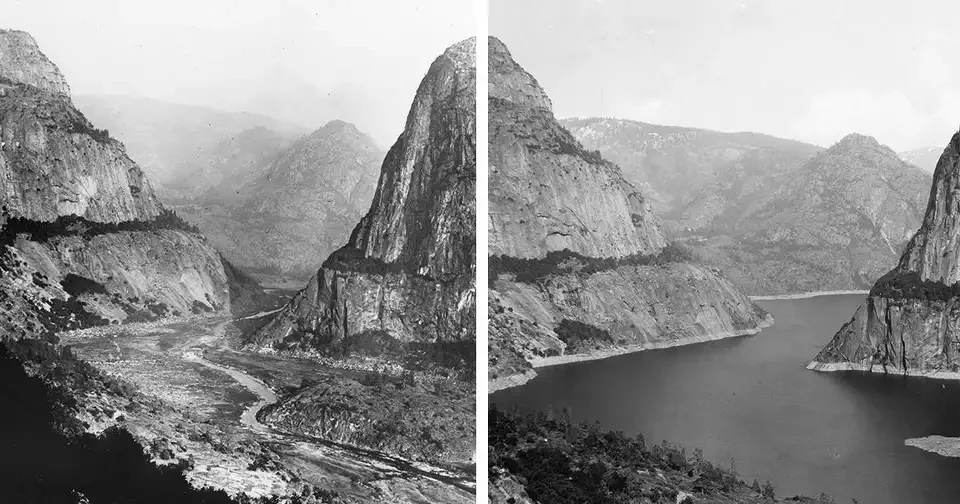

Throughout this period, the Hellenophiles of San Francisco dreamed of aqueducts: piping fresh water from the Sierras down into the Bay, and harnessing the cataracts for hydroelectric power. In the aftermath of the 1906 earthquake, the city’s need became acute: and so calls intensified, as told here, to dam the Hetch Hetchy Valley in Yosemite. Hetch Hetchy was a pretty (albeit mosquito-filled) valley which had been inhabited for thousands of years by Indian tribes; John Muir summed up the mood of many early environmentalists in 1912 when he wrote:

“Dam Hetch Hetchy! As well dam for water-tanks the people's cathedrals and churches, for no holier temple has ever been consecrated by the heart of man.”

Nevertheless, the damming began in 1914. Hetch Hetchy’s groves were washed away as a sacrifice to fill the reservoir, which first supplied the city 167 miles to the west with water in 1934. And thus was made another sacrifice for San Francisco’s growth and security.

Hetch Hetchy, before and after - SF Chronicle

Without oil, coal, or hydroelectric power, the nineteenth-century founders of San Francisco were left with little choice: hardwood forests from the Pacific to Nevada were devastated to feed the new industrial machine. By 1878, Lake Tahoe was laid bare. A reporter called the mines "the graveyard of the Sierra forests", and mining attorney Grant H. Smith reported that "the Sierras were devastated for a length of nearly 100 miles to provide the 600,000,000 feet of lumber that went into the Comstock mines, and the 2,000,000 cords of firewood consumed by mines and mills up to the year 1880." Saruman himself could only aspire to the ambition and callousness of those early builders.

The summit camp of the Carson and Tahoe Lumber and Fluming Company - Online Nevada Encyclopedia

That San Francisco’s growth had significant environmental impact is not, perhaps, surprising. James C. Flood, the backer of a project to pipe Lake Tahoe's waters to the Sierra mines, spoke for many in 1873 when he wrote "Everything can be done nowadays; the only question is - will it pay?" Economic concerns were paramount: environmental, much less social, issues, were far less important.

But while some people did get very rich from California’s minerals, the asset class did not pay. As Brechin has it, "the Comstock Mines produced an estimated $350m in twenty-five years of activity, but only five of its hundreds of publicly traded mines paid more in dividends than they collected in assessments." Alexander Del Mar, a mining engineer and director of the US Bureau of Statistics, said at the London Chamber of Commerce in 1890 that:

The Comstock was probably the richest lode ever discovered, and consisted of both gold and silver. It yielded the enormous sum of £60,000,000; yet it cost no less than £300,000,000.

And yet the mines catalysed the growth of the Bay Area as an economic engine.The value of the Gold Rush was not so much in the metal itself as in the development it necessitated; once catalysed, industry and finance grew symbiotically. The quest for precious metals drew together the foundries of SoMa and the financiers of Nob Hill; the picks and shovels built a new city.

This history raises a simple question: was it worth it? Tahoe, Hetch Hetchy, the Yuba River: their sacrifice is no less real than the city they helped build. Sit in Alta Plaza Park, and look out over the city: are you grateful for the choices of those nineteenth-century builders? Would you have done the same? The question is not an idle one: America faces it today. As America seeks to disentangle itself from Chinese control over global supply chains, while demand for power and compute skyrockets, its leaders must decide how - and whether - to use its abundant natural resources.

It’s worth considering one more piece of history. In June 1968, Arco, a relatively small independent company, struck oil in Prudhoe Bay, Alaska. Unable to capitalise alone, Arco shared the reserve with BP (owning 52%) and Exxon. But, as Anthony Sampson’s book The Seven Sisters has it,

Exxon, having found its Alaskan oil, was in no hurry to get it out, since they had ample and far cheaper supplies in Arabia and Iran... Arco and BP were desperate to push ahead fast; but Exxon were moving very slowly…

Intense opposition to the pipeline was now to come from a completely different quarter. Conservationists on the West Coast discovered that the proposed pipeline would transform the wild life of the whole region; the warm oil would create a wide river in the middle of the ice, thus preventing the migrations of cariboux. The conservationists were strikingly successful, to the growing worry of BP and Arco, who were waiting thirstily for the oil. But Exxon still appeared unconcerned and the suspicion arose in the minds of several BP men: might Exxon be secretly backing the conservationists, as an excuse to delay the production of the oil?

The protests of the ecologists set back the transporting of Alaskan oil by four years and the Alaskan alternative was too late to save the West from its dependence on OPEC when the crunch came. It was not until the energy crisis had broken (in 1973) that the objections were rapidly overruled."

In the face of economic necessity, the field finally became operational in 1977.

Ernest Scheyder’s 2024 book The War Below poses this question again and again. From the Arizona to Alaska, Minnesota to Nevada, The War Below tells the story of the 21st-century mines that the United States is not digging. The basic theme of the book is this: a promising mineral opportunity is established, and then activists - whether cultural or ecological - attempt to derail the project. These attempts have been extremely successful; as a result, the US is failing to exploit its mineral resources, with consequences for both economic growth, national security, and the green transition.

The examples abound. The central motif of Scheyder’s book is Rhyolite Ridge, a Nevada site which boasts significant lithium and boron reserves. A 2020 Definitive Feasibility Study projected lithium production costs of $2,510 per tonne, compared to an industry average of ~$7,000 per tonne.

However, the ridge is also home to the world’s only population of Tiehm’s buckwheat, a yellow-flowering plant that seems to enjoy the ridge’s lithium-rich soil. The plant has become a cause célèbre to environmental activists. When Patrick Donnelly first visited the ridge, he “decided there and then to try to fight for this rare, odd flower, no matter the odds... 'What is religion but finding meaning and purpose in the void of life? I find the mystery of life is unlocking biodiversity, and that's how I connect with nature.'” Donnelly “vowed to stop the full mine from operating were even one flower harmed.”

Patrick Donnelly: “The flowers were blooming, and I got hooked. It's a very charismatic plant when it's flowering”

ioneer, the company which owns the mining rights to the site, has made great efforts to accommodate the perverse preferences of this benighted shrub. ioneer has been “investing millions of dollars to hire full-time botanists, rent greenhouse space, and study soil composition, none of which was a traditional investment for mining companies.” My English readers may, perhaps, be reminded of bat tunnels and fish discos.

James Calaway, executive chairman of ioneer, said “We are prepared to do whatever is necessary to make this mine coexist with Tiehm's buckwheat.”

James Calaway, executive chairman of ioneer, also said “That Patrick Donnelly is a son of a bitch. And you can quote me."

Brian Menell, a mining investor, put it neatly when he said:

We need government to say, 'Sure, we love wildflowers, and we're going to respect environmental and social governance standards, because that's part of our culture.' But at some point, we're going to say, 'Mister wildflower group, you had your say, and now go and shut up. We are going to develop this mine, even if we destroy the habitat of a wildflower, which everybody would regret. It's better than destroying the world with climate change.

Patrick Donnelly supposedly thinks this view is "a bit crass"; I think Brian is spot on.

The crucial thing to understand about the anti-mining lobby is that if it’s not one thing, it’s another, over and over, moving the goalposts to find some reason to object to a site.

Rio Tinto’s Arizona Resolution Copper mine was discovered in the 1990s. It’s estimated to contain eighteen million tons of copper, which was worth ~ $190 billion in November 2025, equal to about 80% of annual global production. Rio Tinto and BHP started the US federal permitting process in 2013; by 2021, they had spent over two billion dollars on the project; in 2022, Wall Street consensus had written the project down to zero.

Why? Because next to the mine site stands a grove of trees known to the Apaches as Chi’chil Biłldagoteel - a place for conducting religious ceremonies to deities known as Ga’an. As Scheyder puts it, “to harvest the copper would require the destruction of a site considered as important to the San Carlos Apache as St. Peter’s Basilica is to Roman Catholics or al-Masjid al-Haram is to Muslims.” For Dr. Wendler Nosie, an Apache activist, “this has become a war between a religious and corporate way of life. We’re all being tested by the Creator. This country is on call.”

Minnesota’s Boundary Waters is a beautiful nature reserve. Tom Vilsack, former governor of Iowa and Secretary of Agriculture 2009-2017 & 2021-2025, said in 2016 that "the Boundary Waters is a natural treasure, special to the 150,000 who canoe, fish, and recreate there each year, and is the economic lifeblood to local businesses that depend on a pristine natural resource."

Yet Ely, the local town, was the product of an 1865 gold rush in which miners excavated 80 million tonnes of rock from shafts and open pits. And within the Boundary Waters lies a copper deposit containing ~2.8 million tonnes of copper, worth ~ $30 billion. In 2014, Antofagasta acquired the site, known as Twin Metals. Not surprisingly, the project generated immense local resistance: as Becky Rom, a local activist, put it:

We don't deny the reality of the green energy transition. But we would have to sacrifice everything we hold dear to have a mine here. There is only one place in America like the Boundary Waters, and it is so important because its waterways are so interconnected. It's not rational to have a mine like this in the region. You can't be the gateway to this pristine wilderness and have copper mining.

This dilemma is partially addressed by the Bureau of Land Management’s Surface Management regulations, which require a financial guarantee sufficient to cover full reclamation costs before operations proceed; the US Forest Service has a similar requirement. These guarantees, known as reclamation bonds, function like a construction firm’s surety bonds. Unfortunately, it seems that no reclamation bond that would satisfy activists like Rom: "How do you bond for the Boundary Waters? It's massive."

Yellow areas are the proposed mine sites. 2020 Harvard paper.

There are four things at play here. First, the reclamation bond is a capitalist solution to capitalist problem, which is not going to be acceptable if your real problem is not mining but capitalism itself. Second, when Rom says “it’s massive”, she’s suffering from scope insensitivity. Regardless of how “massive” the Boundary Waters are (and to be fair, they’re more than one million acres), I suspect that a trillion-dollar reclamation bond would in fact be sufficient to clean them up; but it’s very difficult to conceptualise and compare numbers at this scale. Per Wikipedia:

In one study, respondents were asked how much they were willing to pay to prevent migrating birds from drowning in uncovered oil ponds by covering the oil ponds with protective nets. Subjects were told that either 2,000, or 20,000, or 200,000 migrating birds were affected annually, for which subjects reported they were willing to pay $80, $78 and $88 respectively.

Rom, and other activists, struggle with the same problem. If Twin Metals contained six times more copper, still smaller than Resolution Copper, would she then be OK with mining? What about sixty times? Six hundred? Their objections are scale insensitive.

Rom hinted at a third objection when she said “there is only one place in America like the Boundary Waters”; just as Patrick Donnelly’s bar for blocking ioneer was “one flower harmed”, Rom is treating money and resources as non-fungible with nature and biodiversity.

Five years ago, I wrote about why this point of view is childish and unserious. Normal people don’t have to make this tradeoff, because that responsibility is reserved for leaders.As Montaigne put it in On the Useful and the Honourable:

So, too, in all polities there are duties which are necessary, yet not merely abject but vicious as well... If vicious deeds should become excusable insofar as we have need of them, necessity effacing their true qualities, we must leave that role to be played by citizens who are more vigorous and less timorous, those prepared to sacrifice their honour and their consciences, as men of yore once sacrificed their lives: for the well-being of their country. Men like me are too weak for that: we accept rules which are easier and less dangerous.

Real leaders confront these tradeoffs head on. San Francisco’s founding fathers saw a growing city with no fuel, and burned Tahoe to make it grow. Today, America’s leaders block mines to protect flowers, lakes, and burial sites. If we’re serious about economic growth, and serious about the second American Century, then America needs to be willing to dig for victory just like its founders.