Chip Futures

This post hit the front page of Hacker News - nice!

People used to be excited about crypto. This was great for traders, because there was just so much trading in crypto. Apart from, like, money laundering for North Korea, the main use case for crypto seems to have been creating new things for people to trade.

Now people are excited about AI. This is less great for traders, because there’s much less trading. Sure, AI has driven changes in public equity prices and created lots of startups, but it hasn’t created anything new for traders to trade.

But many traders are also interested in matrix multiplication, and so some of these people are starting to ask: can we financialise chips and compute?

At the moment, you can really only buy these things on the spot market or lock in a long term contract. Is it possible to create a liquid market for options, futures, and other more esoteric derivatives, to give people financial exposure to the underlying assets? Who’s going to be the FTX of AI?

I’m not an expert on either semiconductors or trading; I’m getting myself into serious Gell-Mann amnesia territory here. But this is a fascinating topic, so I’m going to write about it anyway.

But in doing so, I’ll restrict myself to the past - and specifically to discussing Enron’s short-lived attempt to trade memory-chip futures in 2001. First I’ll give a bit of background on the semiconductor industry; then I’ll discuss what happened and what, if anything, we can learn from it.

Chips Put Chips In Pockets

The semiconductor industry is massive: $45bn revenue in 1988, $204bn in 2000, and $574bn in 2022. It breaks down into three main segments: memory, microprocessors and logic. Memory chips accounted for 34% of total revenue in 1996, and 30% in 2017. The two main types of memory chips are DRAMs and NAND flash.

DRAMs manage data, but require power.

NAND flashes store data, and don’t require power.

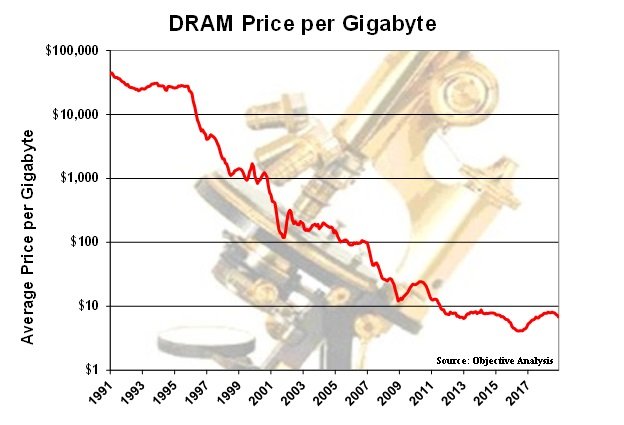

The DRAM market is 1.2-2x bigger than NAND flash, but it’s cyclical, and prices are very volatile. It works a bit like the oil industry: companies reinvest their profits into capex for next-generation chips, and that creates a glut that drives down prices. But it’s actually even more volatile than the oil industry, because chip manufacturers can’t scale back production - they have to operate fabs at 100% capacity.

It’s a brutally competitive industry, and has consolidated significantly over the past 30 years. It’s currently dominated by three giant firms: Samsung ($365bn market cap, Korea) Micron ($118bn, USA) and SK Hynix ($91bn, Korea). Small firms go bust or get bought in a downturn - for instance, Texas Instruments sold their memory chip business to Micron for $800m in 1998.

Moore’s Law drives down memory costs - there’s a learning curve.

Silex Quondam Silexque Futurus

A Forbes article called DRAMs “boring commodity technology that is largely taken for granted”; that means you can swap out a Samsung DRAM for an equivalent Micron one without noticing the difference.

On one side of the DRAM market you have the chip manufacturers; on the other, you have Dell and Compaq and GE, people that make laptops and kettles and car radios. And so the market’s inherent price volatility implies demand for some way to hedge out price risk.

There are two basic ways to do this: forwards and futures. See here for more details, but the key points are:

Forward contracts are negotiated individually; futures are standardised

Forward contracts are often settled with physical delivery of the commodity; futures are normally settled financially (by paying the difference between the contracted price and the spot price at the time of expiry.

If all you want to do is hedge price risk, then futures are better than forwards.

Today, you can trade oil futures; you used to be able to trade egg futures, onion futures, and Maine potato futures; but some commodities have never had a futures contract.

DRAMs were and are the best candidate in the entire semiconductor industry for commodity futures.

In 1989, the San Francisco-based Pacific Stock Exchange proposed a DRAM futures market; the Minneapolis Twin Cities Board of Trade were also thinking along the same lines. The PSE submitted an application to the CFTC to start trading by Q2 1990, but it went nowhere.

In 2001, Enron was fresh from making markets in gas and power, and was looking to find ever more esoteric places to become a middleman - even the rates paid to publishers by advertisers! Buoyed by the dot-com boom, they announced a plan to create a DRAM futures market, as the first step towards making markets for a whole range of computer components, including LCDs.

“The [DRAM] chip market is a boom or bust cycle, with prices very high or very low. It's the perfect market. And Enron has the credibility.

…

We'd like to hedge maybe 60% of a computer, if possible, in the long term. That's our plan."Kenneth Wang (director of Enron's global semiconductor group), 2001

This also went nowhere - and Enron entered bankruptcy in November 2001. Because the firm booked all its future revenues up front (using mark-to-market accounting) and was compelled by Wall Street to show steady 15% year-on-year earnings growth, Enron was desperate for new projects to finance - in order to book those revenues and hit earnings targets. Each year, the pressure ratcheted up; and so I think the attempt to create chip futures is best understood as a last-ditch attempt to find a new market to enter - rather than a genuine belief in the soundness of the market.

But in 2001 Buckaroo.com, a broker in the secondary market for DRAMs, proposed something similar; and in 2003, a US group called SFX and a Singaporean group called SGX independently did the same thing. None of their attempts got off the ground. No DRAM futures were ever traded.

In August 2004, an English entrepreneur filed a patent for technology to create a DRAM futures exchange; and, remarkably, in March 2004, a patent was filed to create a futures exchange in fab capacity for TSMC. Nothing came of these either!

So why is this such a hard problem? Well, there are three main challenges for anyone looking to create a futures market.

The unit-of-sale problem

Liquidity

Regulation

The biggest reason DRAM futures failed was the unit-of-sale problem. Liquidity was an issue too, but to a lesser degree. And all this happened in a lax regulatory environment; since Dodd-Frank, it’s much harder to do anything with derivatives. For that reason, it seems unlikely that anyone will ever manage to build a chip futures exchange.

Unit-of-Sale

To create a futures contract, you need:

The definition of the underlying commodity (e.g. Brent, WTI)

The contract unit (e.g. 100 troy ounces, or 1,000 barrels)

The legal terms and conditions.

Getting this done is manageable for agricultural or mineral commodities - for instance, the NYMEX introduced standard oil futures in 1983. But for chips, the unit-of-sale problem seems insurmountable, primarily because new chip models come out every few years.

In 1989, the PSE proposed trading in 256 KB and 1 MB chips.

In 2001, Enron proposed a contract unit of 25,000 128MB chips.

In 2003, a Singaporean exchange called SGX proposed a contract unit of 10,000 256MB chips. You can read the details of that contract here.

You can see today’s spot and forward contract DRAM prices here; the listed chips are 4GB and 8GB. This dynamic alone makes it really difficult to build a sustainable futures exchange. But there are other problems:

Size isn’t everything; other attributes matter too.

As analyst Sherry Garber put it in 2001, “It's impossible to come up with a so-called commodity DRAM with fit, form, and function that serves all memory applications”; in 2003, she said that “you can have a standard density, a standard type, and a standard configuration, but you can have infinite combinations of those”.

The SGX contract is actually for a “256Mb Double Data Rate Synchronous DRAM, 32M x 8, PC266 and above, 66 pins TSOP2, taped & reel.”, with a specific SKU for Samsung, Micron and Hynix. At this point, we’re not trading a commodity, we’re trading a specific product.Market participants didn’t want to admit that their chips were commodities.

For instance Tom Quinn, a Samsung VP based in San Jose, commented in 2001 that: “DRAM is not perfectly fungible; It's not like if Compaq doesn't want it, you can push it to Dell.”

But I think he was being disingenuous. Someone involved in the 1989 effort told me that it was the manufacturers, not Compaq and Dell, who didn’t want to admit that their products were interchangeable. That makes more sense - Dell would really like to commoditise their inputs, in order to have suppliers compete on price.

As a result, it makes sense that consumers of microchips would be more willing to engage in a futures market than manufacturers.

So there’s variation over time between chip sizes, and also within chip sizes, based both on technical specs and (to some extent) the OEM themselves.

“I would think trading in futures on D-RAM's is a little nuts. If it's an attempt to dampen availability swings, every cycle has a different product in it. Does the Pacific Stock Exchange intend to trade in futures on every hot new product the chip industry puts out as it goes through its boom-bust cycle?”

Charles M. Clough, president of the biggest semiconductor broker on the West Coast (and hence someone with an angle!), 1989

“The problem is that DRAMs are an unstable commodity that undergoes a wide variety of fundamental product changes over time. We believe the inherent instability of the offering renders forward contracts impractical”

Dan Scovel, (industry analyst commenting on Enron’s proposal), 2001

“It's such a logical idea–in theory, it's brilliant, but it just doesn't work. DRAM is a natural candidate for futures trading, because it's the most commodity-like of all semiconductors, but it's not a pure commodity.”

Grant Johnson (industry analyst), 2003

Liquidity

Exchanges are great, because they make 1. trades happen faster, and 2. spreads tighter. But to make them work, you need people on both sides who want to hedge out price risk, plus speculators/market makers. Ideally, you want a fragmented set of buyers and sellers.

Therefore, the increasing consolidation among DRAM manufacturers has made the industry less suitable for a futures exchange. In 1989, a PSE spokesman said that the same 256MB DRAM chip could be produced by 17 different manufacturers; today, that number is effectively down to 3. If one side of the market is too consolidated, then it’s very difficult to build a futures market:

Oil derivatives weren't a complete novelty: futures and options had existed a century earlier, in the years after commercial production began in the US in 1859. For a brief period, oil futures were traded on at least twenty exchanges across the US. But the primitive market for oil derivatives like the spot trade in physical oil came to an end when Rockefeller won control of the industry.

Jack Farchy & Javier Blas, The World For Sale

Rockefeller’s Standard Oil established a near monopoly on pipelines, refining, and retail distribution; and so the wildcatters and production companies who took on the risk of striking oil in the first place were firmly in the position of price-takers. If you’ve got a monopsony, prices can be whatever you want them to be - who needs futures?

As a rule, marketplaces will find it easier to attract one side of the market than the other. And in theory, both sides should benefit; just as nickel manufacturers buy nickel futures, it should have made sense for Samsung to buy chip futures. But in the case of DRAM futures, the challenge was to get the manufacturers on board.

For instance, a Texas Instruments spokesman wrote in 1989 that:

“We're trying to stabilize the market, but rather than go with a futures market, we're going to the core of the problem and working more closely with customers. I don't see how this could benefit us right now.

In other words, he was happy to ink bilateral forwards contracts; he didn’t want futures.

And in 2003, a Micron spokesman said this:

“We typically don't adjust production based on market needs from a cost perspective. We generally run at 100% capacity to keep our fixed cost down.”

The second statement makes sense; it makes sense for oil wells and diamond mines to reduce production of a finite resource in order to prop up prices, but that’s not the case for semiconductors.

The first statement is less clear to me. I think a producer might prefer forwards to futures for two main reasons:

Customer relationships: producers don’t want to sell a commodity, they want to sell a personalised product to a customer with whom they have a long-term relationship. Differentiating on things other than price keeps prices higher. This argument is of course much stronger if the futures exchange doesn’t effectively solve the unit-of-sale problem.

New entrants: if producers have direct customer relationships, they don’t want to let someone else take a cut; and even worse, they don’t want to give speculators room to manipulate the market. For instance, after Siegel and Kosuma manipulated the Chicago onion futures market in 1955, Congress prohibited onion futures at the request of the growers.

So, descriptively, it seems that the 1989 and 2001 efforts to create chip futures failed because they didn’t get chip manufacturers on board. This might just be what the kids call a skill issue - it’s possible that neither PSE nor Enron were very good at negotiating with the chaebols (I learned that word this week and I’m very pleased with it).

The chip market is idiosyncratic; typically, futures markets for agricultural commodities have more difficulty convincing consumers than producers. But when Enron set out to reform the gas market in the late 1980s, they also struggled to sign up producers. Although oil futures were traded on the NYMEX from 1983, 75% of American natural gas changed hands in the spot market in the last few days of the month. Both producers and consumers took on significant price risk, and neither used forward contracts. Enron’s solution was not a bona fide exchange, but rather to act as a middleman, capturing a spread - this was the Gas Bank.

But while consumers - e.g.utilities piping gas into homes - were happy to sign contracts in order to guarantee supply, producers were much less willing. The mostly Texan exploration and production (E&P) companies were inveterate optimists, and expected prices to rise indefinitely. They took the same approach to risk management as another Southern legend:

One time the macro men feared that the markets would turn against their European bond position in the short term, and they advised [Julian] Robertson to protect Tiger from losses by putting on a temporary hedge.

“Hedge?” Robertson retorted angrily. “Hey-edge? Why, that just means that if I’m right I’m going to make less money.”

“Well, that’s right,” the macro men answered him.

“Why would I want to do that? Why? Why? That’s just dirt under my fingernails.”

That was the end of that attempt at risk management.

Sebastian Mallaby, More Money than God

However, there was something of a credit crunch in Texas at the time, and banks were unwilling to lend to the E&Ps. As such, Jeff Skilling offered to pay producers up front for the value of the contract - in effect creating a mixed swap, adding a bet on interest rates to the bet on gas. With the Gas Bank offering real financial help, the producers were much more interested, and Enron was able to successfully build out the gas futures market.

Regulation

In 1974, Jimmy Carter created the Commodity Futures Trading Commission. The CFTC’s predecessor, the CEA, only had authority over agricultural commodities; the CFTC would regulate all exchange-traded futures.

That left some pretty significant grey areas - including forward contracts. While the CFTC got some oversight over market participants, they had no jurisdiction over the OTC forward contracts that sophisticated participants engaged in. And crucially, one flavour of OTC forward contract was interest rate swaps. If one party has floating-rate debt, and one party has fixed-rate bet, banks could facilitate an interest rate swap between them in order to hedge the risk; but without CFTC oversight, these transactions were unregulated.

By the time the government realised what was happening in the swaps market, it was so big that nobody was sure whether it could be safely unravelled without causing a mass sell-off. And so off-balance-sheet swaps and derivatives remained beyond the reach of the CFTC.

Most of Enron’s trading in the 1980s and 1990s consisted of these OTC derivatives; since they didn’t happen on the NYMEX or Chicago Merc, the CFTC had no idea what was going on. Furthermore, the 2000 Commodity Futures Modernization Act confirmed the exemption of digital futures exchanges from CFTC regulation.

That was fantastic, because on November 29, 1999, Enron had launched Enron Online - a digital marketplace for energy futures contracts. Rather than phoning someone up, traders could trade by hitting a button - and in every single trade, Enron, was the counterparty. Given that context, the exemption makes more sense: Enron wasn’t really running a digital exchange for third parties; it was acting as the counterparty for lots of digitally-executed forward contracts.

In 2000, this all looked great. The dotcom bubble was expanding, Enron was a growth stock, and American commerce was booming. But Enron’s collapse, and the subsequent unravelling of tens of billions of off-balance-sheet swaps and derivatives, changed public perceptions somewhat.

That negative attitude to swaps was exacerbated by the collapse of the energy hedge fund Amaranth in 2006; and in 2007, the Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations released a report titled ‘The Role of Market Speculation in Rising Oil and Gas Prices: A Need to Put the Cop Back on the Beat’. It blamed speculation in unregulated commodities futures for raising consumer prices, and recommended the closing of the ‘Enron Loophole’ in the 2000 CFMA - which left electronic futures exchanges unregulated.

Of course, worse was to come - in the aftermath of the 2008 GFC, “swaps”, especially when they were of the credit default variety, became somewhat non grata. And so the 2010 Dodd-Frank Act, one of the main legislative responses to the financial crisis, finally brought OTC derivatives under the purview of the SEC and CFTC. This allows them to audit and approve individual contracts, imposing things like position limits.

The point of all this is to say that 1989 and 2001 were particularly good times to be an innovator in commodity futures. Not only was the CFTC relatively toothless, the internet was still the Wild West. Post Dodd-Frank, these things are much more tightly regulated.

Conclusion

My takeaways from the history of DRAM futures are straightforward:

People tried to make the market;

They never solved the unit-of-sale problem;

They never got chip manufacturers on board;

And all this happened in a favourable regulatory environment, which is now gone.

Kenneth Wang’s ambition (hubris?) was striking: “We'd like to hedge maybe 60% of a computer, if possible, in the long term. That's our plan.” This is the sort of thing FTX went around saying; the intellectual purity of the idea was what made it so Enron. Of course this market was dumb; of course he would be the man to solve it. With logic, maths, and stacks of cash (well, in Enron’s case, not much actual real cash), messy reality could be tamed.

It didn’t work out for them. But the lesson, I think, is not that taming reality with logic, maths and cash is a bad idea: it worked for Uber! Rather, I think the story of DRAMs sets a lower bound; if it didn’t work in that market, then you better know why your market is better suited for financialisation.

Fortis vero animi et constantis est non perturbari in rebus asperis nec tumultuantem de gradu deici, ut dicitur, sed praesenti animo uti et consilio nec a ratione discedere.

Quamquam hoc animi, illud etiam ingenii magni est, praecipere cogitatione futura et aliquanto ante constituere, quid accidere possit in utramque partem, et quid agendum sit, cum quid evenerit, nec committere, ut aliquando dicendum sit: “Non putaram.”But it takes a brave and resolute spirit not to be disconcerted in times of difficulty or ruffled and thrown off one's feet, as the saying is, but to keep one's presence of mind and one's self-possession and not to swerve from the path of reason.

Now all this requires great personal courage; but it calls also for great intellectual ability by reflection to anticipate the future, to discover some time in advance what may happen whether for good or for ill, and what must be done in any possible event, and never to be reduced to having to say “I had not thought of that.M. Tullius Cicero, De Officiis