Why Founders Should be Less Ambitious

I mentioned the thesis of this essay to a friend, and they told me it was second-year university economics. I didn’t take second-year university economics, so I feel no shame in making the argument.

Right now, I’m starting a SaaS company; we make a piece of software that helps mobile game companies sell ads more profitably. This is an attractive business idea to me because 1. I know the domain well and 2. I genuinely think we can make it work; I think we can take the boring and repetitive process that I used to do for a living, and add a piece of software that makes it much less boring and much more productive.

But I know I’m not currently aiming at the largest TAMs in the world. There are only 500-1000 possible customers for our product (as currently defined).

I have been told by a VC friend that I’m not being ambitious enough; I should try to start a unicorn company. Should I?

Imagine you’re offered two bets:

Bet A is a 10% chance to win $1,000

Bet B is a 1% chance to win $10,000

Which should you take? Strictly speaking, the expected value of the two bets is the same; but it’s a generally-accepted principle of economics and psychology that wealth has a diminishing marginal utility; a marginal dollar is worth less to a rich man than a poor man. This means that Bet A is much better that Bet B.

There’s a fairly famous Twitter thread that resurfaced in November 2022 amidst the fallout from certain other events. In this thread, the author introduces an idea:

SBF goes on to argue that this reasonable conclusion doesn’t apply to him, because his utility function depends on his contribution to charity. Since the scale of wealth required to address the world’s problems is so massive that the wealth of any individual pales in comparison, he actually has a linear utility function:

I think this idea of EV(log(W+$1,000,000,000,000)) creates a disconnect between founders and VCs.

If we can assume that a founder has a utility function, then log(wealth) probably plays a significant part in it. But the VCs investing in a founder’s company are diversified; and so when VCs think about the individual companies in their portfolio, they think of them as one amongst many; closer to log(W+$1,000,000,000,000). As such, founders have logarithmic utility functions, but VCs are much more linear.

This means that when a founder is faced with a choice between a high-risk, high-EV option and a low-risk, lower EV option (e.g. 1% chance of $10,000 vs. 10% chance of $900), the founder ought to take the low-risk bet. But the insignificance of individual companies at the fund level, especially for seed investors, means that VCs ought to push founders towards the risky option.

That conclusion surprises me a bit; in my head, board members are sober and sensible, and I hadn’t thought much about misaligned operational incentives between founders and VCs. This leads me to think about two further questions:

Over-extension

Many tech companies, but most notably Google, have been doing layoffs recently. This is, of course, driven by the macroeconomic climate, but when I think about this process, I think about Shopify’s 10% layoff back in July 2022. Here’s how Shopify CEO Tobi Lütke announced the decision:

Shopify has always been a company that makes the big strategic bets our merchants demand of us - this is how we succeed. Before the pandemic, ecommerce growth had been steady and predictable. Was this surge to be a temporary effect or a new normal? And so, given what we saw, we placed another bet: We bet that the channel mix - the share of dollars that travel through ecommerce rather than physical retail - would permanently leap ahead by 5 or even 10 years. We couldn’t know for sure at the time, but we knew that if there was a chance that this was true, we would have to expand the company to match.

It’s now clear that bet didn’t pay off. What we see now is the mix reverting to roughly where pre-Covid data would have suggested it should be at this point. Still growing steadily, but it wasn’t a meaningful 5-year leap ahead. Our market share in ecommerce is a lot higher than it is in retail, so this matters. Ultimately, placing this bet was my call to make and I got this wrong. Now, we have to adjust. As a consequence, we have to say goodbye to some of you today and I’m deeply sorry for that.

Would it have been better for Shopify not to have hired so aggressively? Sure, they got unlucky - but were their calculations wrong?

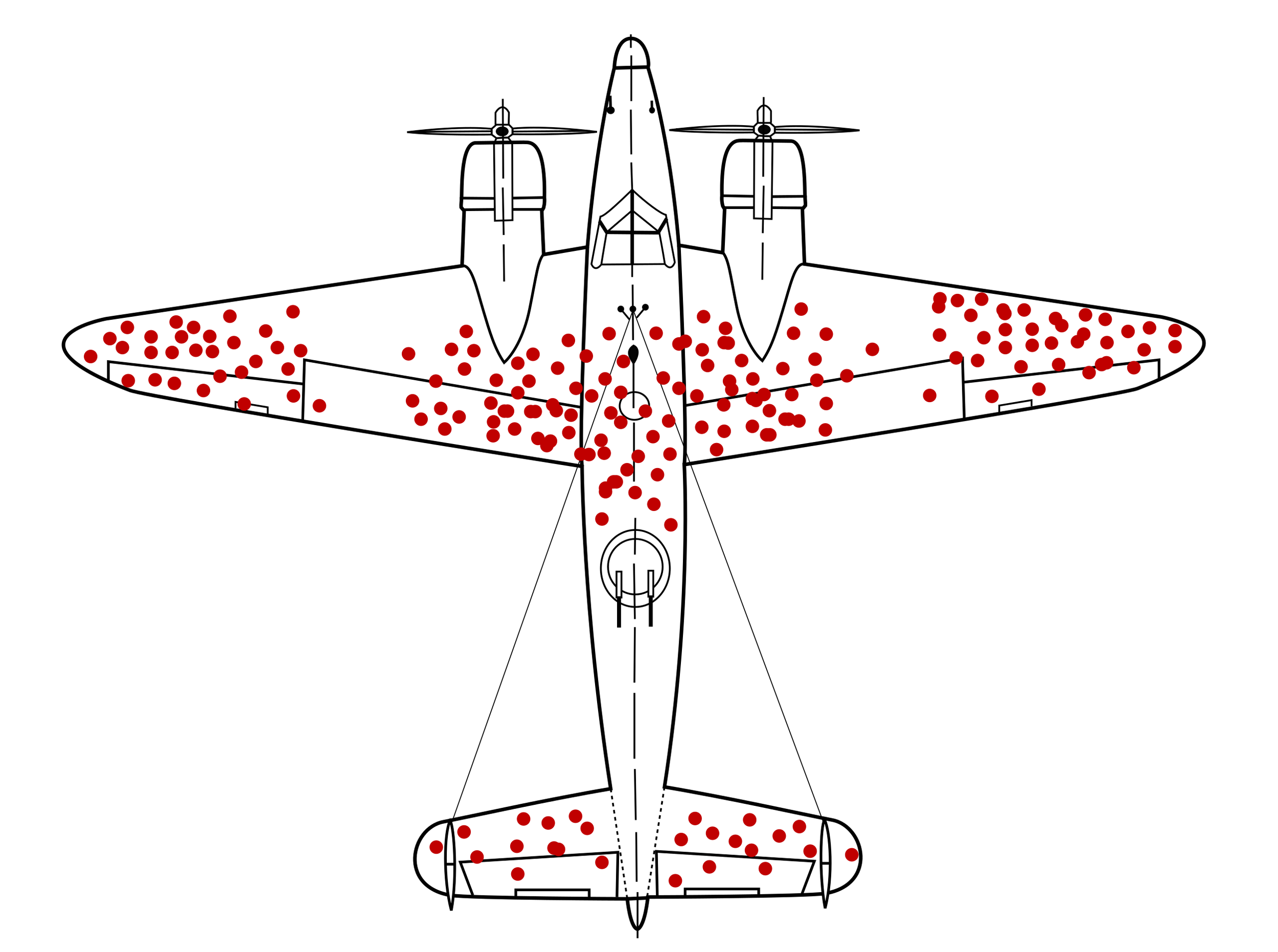

One argument in favour of the bet Toby Lütke made is survivor bias: we only hear about layoffs at big companies, but big companies are much more likely to need layoffs. Successful companies outscale their competitors, hiring aggressively to drive other companies into the ground. If Shopify hadn’t scaled to match COVID demand, then they would have lost market share to competitors, and never got to such a scale in the first place.

But maybe part of the story here is about a disconnect between the attitude of those managing a portfolio and a single company. Maybe Shopify’s “big strategic bets” served the interests of its investors (i.e. the public markets) more than its founders and employees?

2. Successful VCs are good at mitigating downside risk

All else being equal, a fund made up of 100 companies with linear utility functions will outperform a fund of 100 companies with logarithmic utility functions. VC firms (and more generally, entire startup ecosystems) need to persuade their companies to be less logarithmic; less happy to settle with a smaller reward. One way they can do this is to reduce downside risk.

I think this mostly comes out in the way that Silicon Valley has, to a remarkable degree, eliminated the stigma around failure. Being a failed founder is no bad thing; just look at Adam Neumann’s ability to raise $400M for his new company.

Matt Levine has something to say about this:

One thing that I like to say around here is that it is good for your career, in finance, to lose a billion dollars. Losing a billion dollars indicates, to your next employer or investors, that someone — presumably someone smart, who had a billion dollars — trusted you with a billion dollars. It shows that you had the ability and nerve to take risks, which is (within reason) an attractive quality in high finance. And presumably you learned valuable lessons about whatever went wrong, and next time you will take better risks and make a lot of money instead of losing it.

I think of this as applying mostly to traders at big banks and hedge funds, but it has broader applicability. Adam Neumann incinerated truly titanic amounts of investor money at WeWork Inc., which was bad, and got him removed as chief executive officer of WeWork. But it was also … impressive?

Perhaps a giant hedge fund with many different portfolio managers wants each individual manager to be slightly more aggressive than their own individual logarithmic utility function would demand; maybe the hedge fund industry as a whole wants this of its traders.

But I think this applies much more to an entire startup ecosystem; if you can persuade everyone to take a lot of high-EV high-risk bets, then on aggregate the system will be more successful. That being said, I think this only applies if we assume the bets are independent; if failures cascade, we get a systemic collapse. It seems to me that financial bets (especially when they involve leverage) are more likely to cause contagion than tech startups; and so maybe Matt Levine’s got it the wrong way round.

My friend is right to tell founders to be more aggressive. The more persuasively he does this, the better his returns will be - and the whole ecosystem will benefit from it. But that doesn’t mean I should listen to him.